Journeying through science, art, education, sustainability, and arriving at the future: of our food

Grow-at-home algae. Future farming. Cellular agriculture. Plant-based meats. Algae-based bacon. Bacteria-grown vanillein. This past few weeks has been a flurry of art-meets-science activity, with a full immersion in a fascinating area: the Future of Food.

After last year of touring schools around the world(!) giving workshops fusing Art, Science and the Future, it was exciting to be entering a period of time which would be fully immersed in London, and bringing some of my interest, projects and passions into my work here. While by weekend/evening/holiday I have been juggling a crazy mix of projects, enterprises and campaigns (while maintaining time for quiet, calm reflection and beautiful relationships), by weekday I have been based at one of London’s most famous institutes of science & technology: Imperial College. For 18 months I have been continuing my research into the cultivation of algae as bio-factories – a potential puzzle piece of our utopia future, fusing technology, sustainability and waste-free, pollution-free, bio-based production.

Production of what? To start with, I was focussing on producing biofuels. Why? Oil bad, biofuel good, right? After taking some time out after my undergrad degree, I had a chance to re-align with my purpose and further, bring my ethics – non-violence to self, others and planet (or in permaculture terms: self-care, people-care, earth-care) – into my work, life, and even diet. I took up a daily meditation practise and shifted my diet to almost entirely plant-based. I’d met people who were doing exactly that, in many shapes and forms – through living and working on a sustainable community in Laos, building a biogas fermenter for a village to supply them with gas for cooking, fellow humans working for social justice, meditation teachers, awesome people living in purpose and passion.

Clay and brick biogas fermentor built at SAELAO sustainable community near Vang Vieng, Laos

Liquid waste post-fermentation = ready to be used as Nitrogen rich fertiliser!

When I returned to the UK, I didn’t know what the next chapter was going to look like for me. Growing up, I had found the gradual narrowing of subject choice and interest in our classic education system more and more tense as the pressure to give up parts of myself and my gifts increased. Three years at university studying intensive Natural Sciences had made it seriously difficult to have time for what Tagore refers to as whole-being learning – integrating all parts of yourself, with time for reflection and space to connect the seemingly un-connectable. This, to me, seems to be at the root of all ideas that hold an element of genius, or novelty – just like at the edge of a forest in forest agriculture: the forest boundary is where exists the most diversity, and productivity for growing crops, and the same lies true for the productivity of ideas and creativity in life.

Back in London, I was open to learning, spreading the things I was learning to others, and trying something different. I decided to return to Science. The synthetic biology movement drew me in, along with biohacker culture and talk of DIYbio – and the strong ties the synbio community has with non-scientists: artists, designers, programmers, chefs, engineers… As well as being underpinned by a common goal: building a more sustainable, equitable world. I couldn’t believe I was finding a niche that encompassed so many aspects of what I was passionate about. I attended synthetic biology focussed The First Day of Tomorrow conference in Paris and joined the London BioHackSpace. I was employed by Imperial College, to work as part of an algal biotechnology research lab with my awesome supervisor, Patrik Jones. The research focussed on engineering algae to pump out out future biofuels... Sounds like a great solution, right? Not sure of whether the purely academic life was for me, turned down the option of committing to a 3 year PhD, and instead jumped at the chance to be a free-form researcher – in a position I’m still hugely grateful to have been granted today.

The Patrik Jones lab (minus a couple members...)

This last year and a half has been one of the periods of greatest activity, learning and creativity of my life. On starting research into alternative options to our fossil-fuel addicted society, I joined Imperial’s Environment group and co-founded Fossil Free Imperial – a political and activist campaign trying to convince bodies of power to take out their investments from fossil fuels. This was my first taste of ‘activism’, and it felt right to be complementing my research in the lab with driving for the social and political system change with the people. I now continue ‘activism’ in other forms that I find more aligned with my life and in my eyes, conducive to change, although Fossil Free Imperial continues to run in the hands of an awesome group of Imperial student campaigners.

The same year, I lived and worked as a live-in mentor for 160 Imperial undergraduates in the absolute crazy house that is first-year undergraduate halls. I joined a troupe of education reformers in 225 Academy as the Science Director and the movement of re-inventing education and creating transformative learning experiences. I created unique and hands-on workshops and curated week-long programmes, supervising projects, which I’ve continued with projects like Brainiac Club and school collaborations. I’ve now repeated and iterated on many of those workshops which I give elsewhere today. Many students we had the pleasure of working with have now re-directed their life to focus on their passions, re-discovered their creativity and drive and decided to use both to help change the world.

Giving a group of 11-17 year olds a workshop on the future of Science and Technology and how to solve world problems (Mumbai, India)

Along the way, partly while devising the above workshops, I found myself somewhat disillusioned with science and technology as a solution for global change, as I’ve learned how much work we need to do on the level of the people, and on ourselves. At 225, I started teaching the practises of yoga and mindfulness, and the impact both (along with diet, mindset, routine and other practises) can literally change the structure of your brain, to live a fuller, happier healthier life. I saw the impact that could be made by inner transformation and inspiring our next generations to joining the movements going on to re-direct our global path from one of exhaustion and destruction. In the lab, my experiments with bacteria were yielding disappointing yields of biofuel.

A couple of weeks ago I was given the chance to give a lecture to Imperial’s synthetic biology undergrad students, and I spoke of my disillusionment with synthetic biology after all of the promises the field had made. My supervisor in the audience laughed as I took the undergrads through my emotional rollercoaster of research in the lab. On one of my slides, I quoted a Tweet that had been published by NewsWeek last year saying: ‘Synthetic Biology was going to change the world and now it’s making vanilla’.

Lecture on becoming realistic with synthetic biology: what's actually going to change the world & provide solutions in sustainability, right now?

Synthetic biology fail? Apparently so according to NewsWeek...

But, I said, perhaps this is not a reason to laugh. It seems to me that synthetic biology has taken the natural progression of any new technology: the Hype Curve trajectory. We set out with moonshot goals and unrealistic timeframes. We decided to tackle a huge and wicked problem, fossil fuels, using a simplistic and technocratic solution. But there are areas where synthetic biology, could help, right now. While the lofty (and somewhat pathological) aspirations of the field are to ultimately control natural life-forms to become ultimately engineerable machines for our manufacture, Nature refuses to be tamed so easily. Bacteria and algae are not pumping out the volumes of biofuels and chemicals that our growing population is hungry for.

However, what really excites me, is their role in the less obvious areas. The niches where the small win can make a big difference, instead of trying to 'save the world' in one big swoop. Artists and designers are joining our teams of scientists to push the boundaries of imagination in how living things could be used, in collaboration, to build sustainable solutions. The discipline of Biomimicry has boomed since Janine Benyus’ Biomimicry was published in 1997. And now, groups of us in labs and institutions are re-directing to apply molecular and bio-engineering in more creative solutions to solve sustainability problems. One of these is the area of food and food waste.

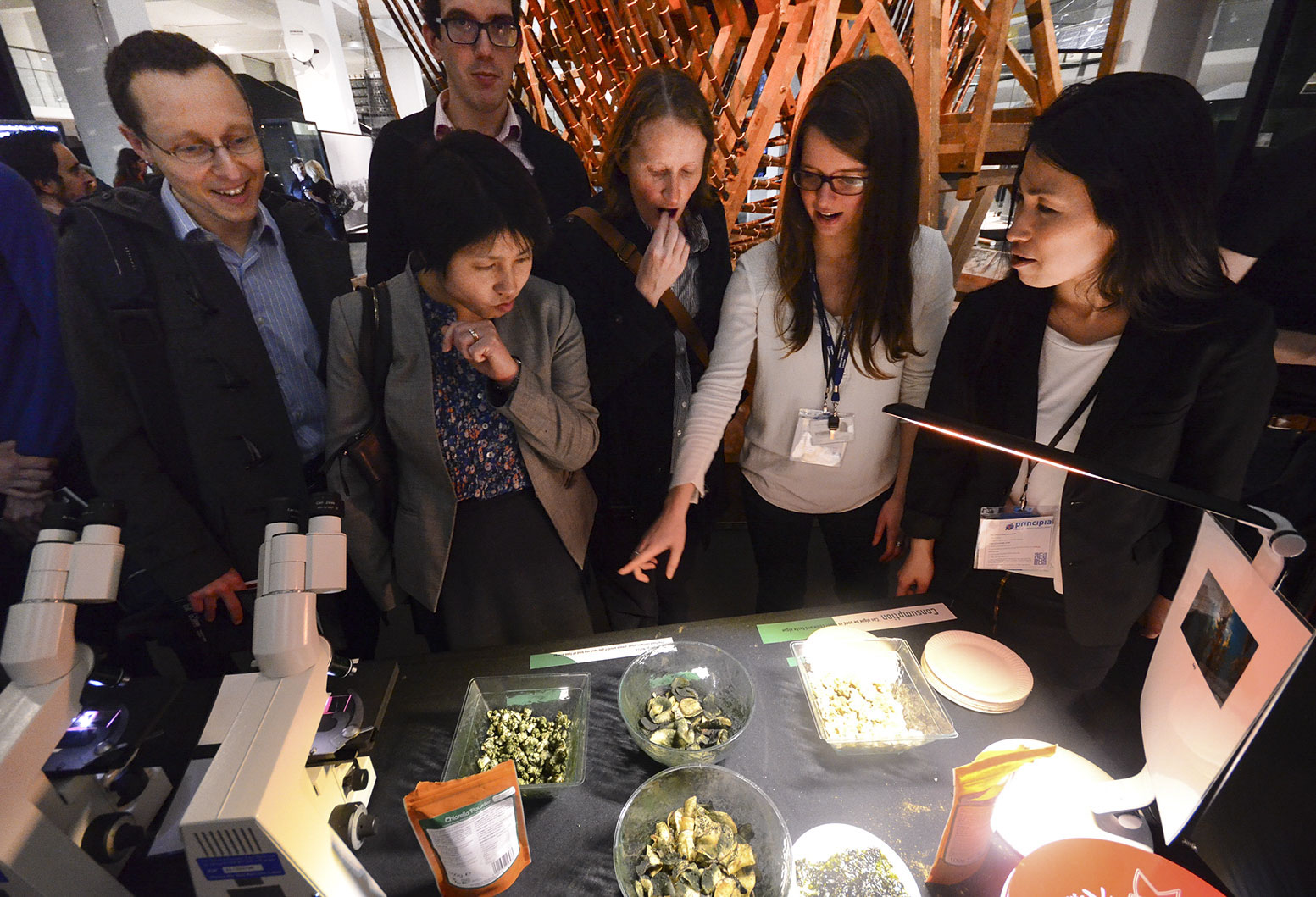

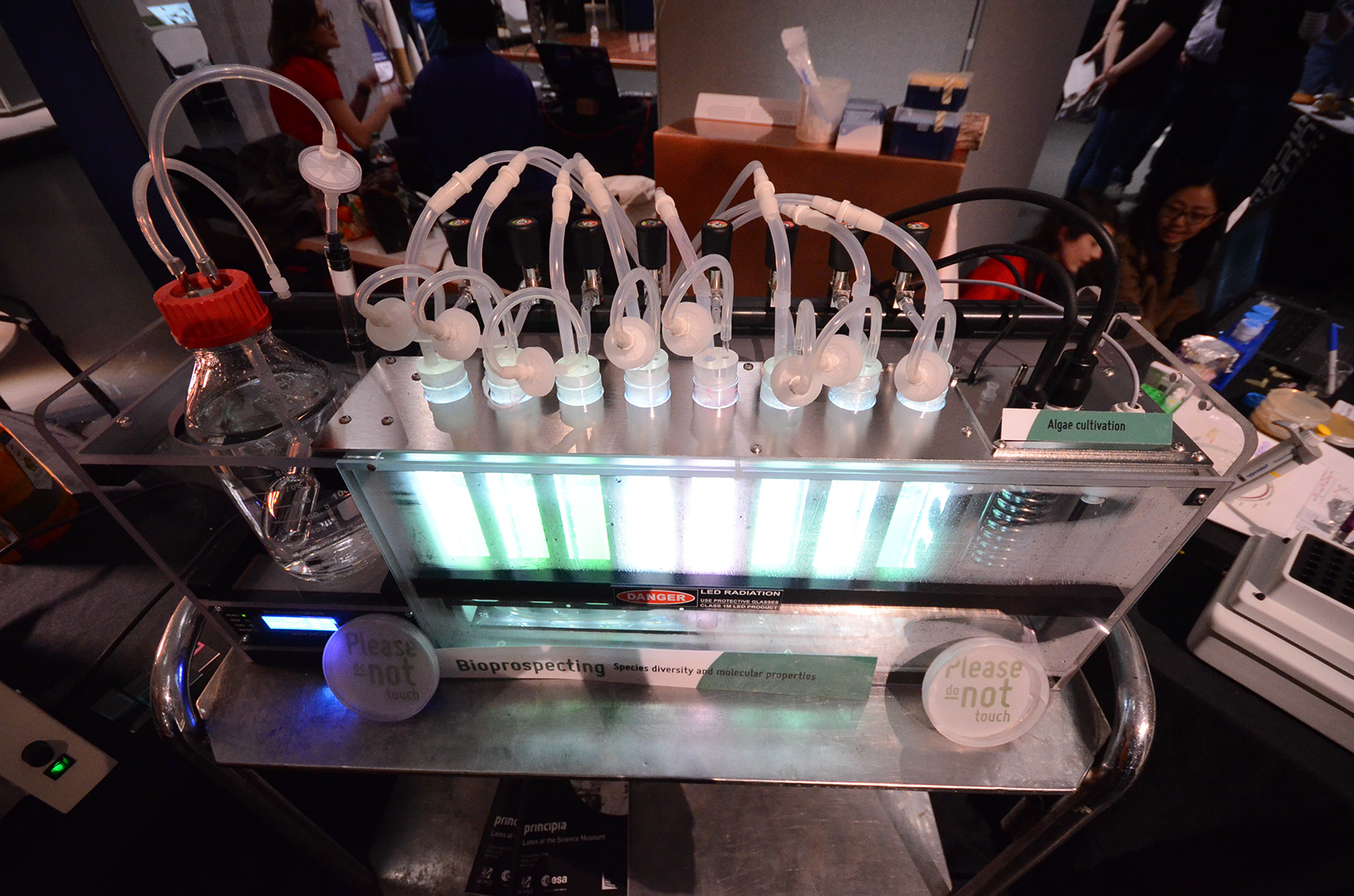

The journey started last December when, along with other members of my lab, we designed and created a multi-sensory exhibition at the Science Museum Principia Lates – exploring how algae could be used to grow food for astronauts in space. Collaborating with biodesigner Marin Sawa allowed us to work directly at the science/art boundary, while I designed experiences to experiment with the taste of different algae, which could then be seen alive under the microscope.

Algae represent a hugely exciting area in the combined effort to create our future of food – able to grow on wastewater and seawater, they can be manipulated in incredible ways to substitute unsustainable foods and engineered in colour, texture and nutrient/metabolic content. The possibilities are endless. Spirulina spp., one more well-known species, has a natural protein content of 60-70%, surpassing most grains, lentils and other protein sources. Instead of complementing the already rich and nourishing diet of the middle-class Westerners, it could be used as a real solution to global malnutrition - and grown using local production.

It was amazing to get stuck right into the task of imagining and shaping the future, opening it up to the public and setting up exhibits and experiments to engage the passers-by, and guide them into questioning the norms of our food systems and understanding what the future may hold. One of my aims in the exhibition was to make it as interactive and cross-modal as possible - as someone who loves making art but finds art galleries often quite mind-numbing, I wanted the audience to get as involved as possible. Creating a two-way interaction also spices things up for the person on the side of giving the exhibition. It's what made me go into giving workshops instead of traditional stand up and lecture teaching.

The public were invited to smell, taste and try different species of algae, sprinkled on familiar foods... Then immediately view their live algae of choice under the microscope, and interact with shaking cultures of different coloured live algae. Discussions ranged from how we could cultivate algae, why they could be more economically and ecologically sustainable compared to crop agriculture, their nutritional content, how we could grow them at home, which metabolites can be engineered and what sorts of funky and unusual characteristics make algae so... funky. As a total bio-nerd I'm constantly surprised at how under-appreciated algae and their weird and wonderful superpowers are... Just check out the latest news of the red algae that tastes like bacon!

Since then, I have had the pleasure of connecting with and collaborating alongside some amazing people all working in this exciting science/art boundary and pushing for a more sustainable, equitable and healthy future of food. And things keep on evolving. One of them is Abi, part-time PhD student at King's working on cellular agriculture, part-time artist troublemaker with whom I'm working with on a number of ideas to bring this food revolution to the public. Cellular agriculture = what it sounds like: growing meat in the lab - in particular, growing steak. Along with my research on algae and plant-based food futures, we're cooking up a really interesting foray into what our food future may look like... And shed light on the current problems are that we're trying to solve. Both living science and ethics through the work we do, our diets and even spare time, it's already been a fun couple of weeks and the next chapter to come holds many possibilities. Check out Future Farm Lab to stay tuned on what we're cooking up!

All of this came synchronously in time with the Science Gallery London's #FEDup season: exploring the broken food systems of society, imagineering the future of food, turning waste to meals, and getting lots of scientists, artists, entrepreneurs, designers, politicians, communicators together to talk about these things. Below you can see photos from one of the Science Gallery's events - where social enterprises like Toast Ale (who are making ale from surplus bread in Hackney) and Jamie's Fifteen came together to create a three course dinner from London's redirected waste food - and we got a taste of the future of protein (it's crunchy!). Another art/science blur occurred when sound engineer/artist Matthew Herbert got involved with his food records at Edible Sound - experimenting with food, sugar other edible materials to create sound that could be used to communicate the ethics and quality of the food being eaten. I don't know how much it speaks to me literally playing with food that could be used to feed those who need it, but as quite a political artist, the discussion that followed explored a lot of controversial themes and went deeper than the initial sugar record suggested.

So what's to come? It seems like this area of work, exploration and creation is a wave that is about to crash: food is such a huge part of every one of our lives, and such a powerful way to take action and make an impact on sustainability and change your footprint on this world. Food gets everybody excited - and brings all of us together. Diet is also the most impactful action you will have on your own life. As the famous quote by Ann Wigmore goes,

"The food you eat can be the safest and most powerful form of medicine or the slowest form of poison".

To heal our food system, we will need to make use of a combination of the latest creations of science and technology (often plant and microbiology science - woop!), our ethical and conscious brains, and return in new ways to ancient wisdom and old 'technologies' - to regenerate land that has been poisoned, make forest gardens and permanent agriculture, while restoring wildlife and ecology to huge swaths of now barren land. It's an exciting, stimulating and urgent place to be positioned. It's also a place of intersection of many different disciplines and cross-modalities that have to work together to be able to progress on solutions to the big mess we've created in the way we farm, treat, grow, package, transport, store, consume, and dispose of our food. And I'm excited to be at that intersection :).